Thu, Jul 22, 2021

Green Rush to Renewables - The Perfect Climate for Corruption

Change is usually driven by standout events, and 2020 delivered the perfect storm. The year started with severe wildfires in Australia and the U.S., and the dramatic momentum did not stop. During 2020, the planet experienced catastrophic flooding, record temperatures, the most active hurricane season on record and the strongest tropical cyclone to make landfall.

2020 was obviously not just the year of extreme climate events. As COVID-19 swept through the world country by country, economies came to a grinding halt as people were asked to isolate to reduce the spread of the virus. Whole industries have shut down and governments have racked up huge debts, supporting furloughed staff and propping up their economies. As vaccination programs are taking effect in some countries, governments are trying to understand where to focus investment as part of their recovery efforts, to generate jobs and deliver significant infrastructure projects.

COVID-19 lockdowns did, however, demonstrate one thing: Behavioral change can have an impact on the environment. For example, emissions in towns and cities around the world dropped within weeks to the levels seen 20 or 30 years ago.

Although COVID-19 has shown the fragility of our ecosystems, social change was brewing before this, and there was an increase in focus on the impact of humanity on our environment. Greta Thunberg’s activism thrust the topic of climate change back into mainstream commentary.

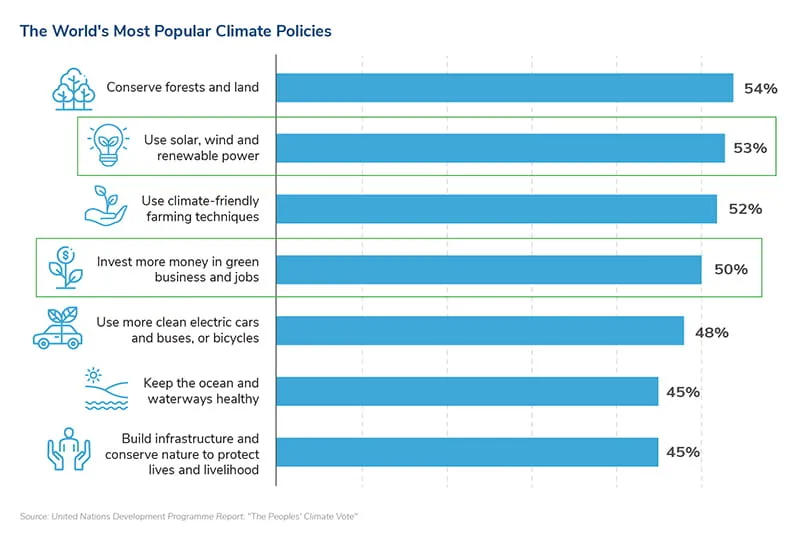

An overwhelming response to a UN global climate poll found that two-thirds of those surveyed said climate change is a global emergency. Renewable energy was the second most popular policy to attempt to address climate change, behind land conservation.1

Many countries are seeing this as an opportunity to invest heavily in renewable energy, as part of their post-COVID-19 policies.

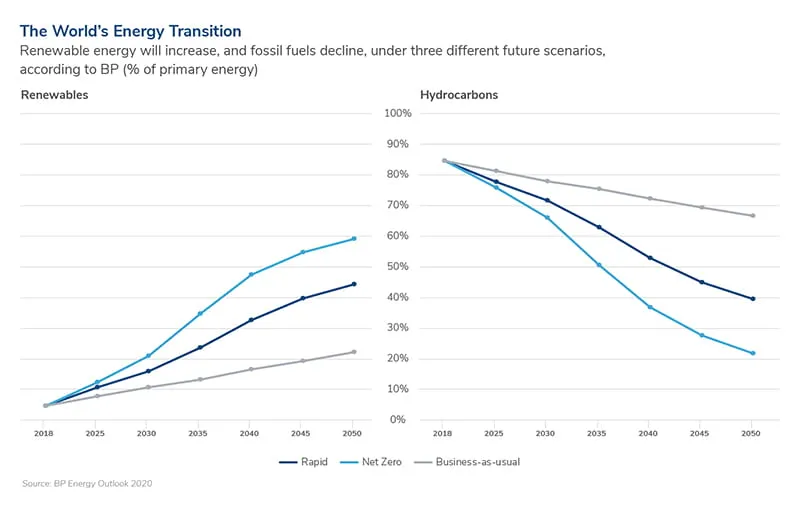

As renewable energy production increases, fossil fuel usage is expected to decline. To achieve a net-zero scenario, fossil fuel usage will need to reduce by 40% over the next 20 years.2

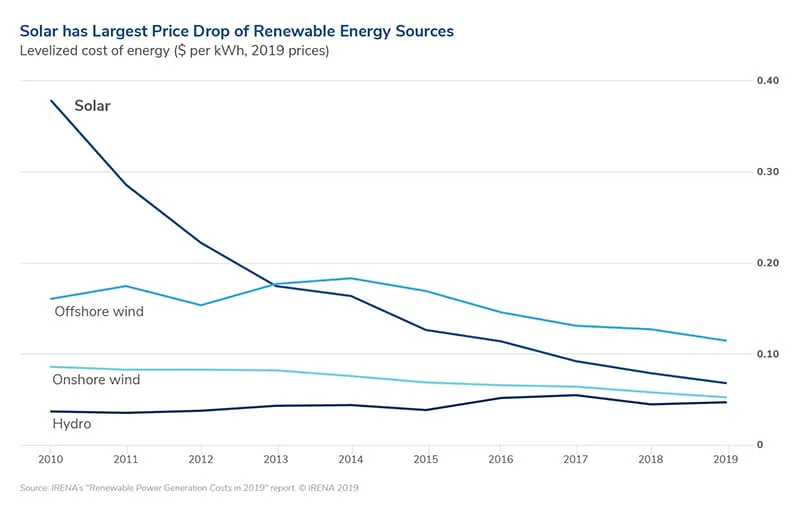

All of the above, coupled with a significant decrease in the cost of renewable energy in the last decade, with wind down 70% and solar down by 89%,3 has led to the start of a green “gold rush.”

It’s A Good Time to Be in The Pick And Shovel Business

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), in 2020, more than 260 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity was added to the previous global total of 2,540 gigawatts, a 10% increase overall, and exceeding expansion in 2019 by almost 50%. Of all new electricity capacity added in 2019, more than 80% was renewable, with solar and wind accounting for 91% of new renewables.4

The financial industries supporting investment in renewables and other environmental, social and governance (ESG) projects have had a busy year; more than $347 billion (bn) was reported to have been invested into ESG-focused investment funds in 2020, with more than 700 new funds being launched globally to deal with the demand from investors.5 In the U.S., whose market is still below the level of those in the EU, sustainable funds attracted $51.2 bn of investment in 2020, more than double the previous record of $21.4 bn set in 2019.6 The newest generation of investors is also on board—Morgan Stanley reported that in 2019, an overwhelming 95% of millennials who were individual investors were interested in sustainable investing.7

According to JPMorgan, the next frontier for sustainable finance is debt that rewards borrowers for hitting ESG targets8; this will help to identify and weed out companies and funds that are simply hoping to profit without actually providing the quoted activities or output. As non-ESG compliant businesses are now perceived as riskier investments, more investors are insisting that ESG factors are included in the due diligence process.

As a result, with more money pouring into the sector, valuations for companies even remotely linked to green initiatives have soared as industry players and investors look to source and acquire companies whose output can be repurposed for use in combatting climate change. For example, a water treatment plant that until recently was worth tens of millions of dollars has seen its value rocket to more than $1 bn based on its output being switched for use in the creation of clean energy from hydrogen.

The current wave of renewable energy activity also includes battery storage, with fast-developing technologies facilitating green energy generation and storage in remote areas traditionally dependent on diesel fuel to generate electricity. As new infrastructure is built quickly, further risks will evolve.

Such a level of frenetic activity on a global scale, with new and inexperienced players who are highly motivated, has created the perfect climate for corruption through which bad actors can seek to profit, often from behind a veil of a seemingly credible corporate facade.

How Corruption Risk is Affecting the Renewables Industry

Inevitably, with such forces at work, the risks of operating in the industry have increased significantly, with the key impacts being felt across all four key areas of the renewables supply chain: manufacturers, distributors, developers and operators. Add in the ongoing disruption to pre-pandemic business models and processes, and the sector is facing an unprecedented set of challenges.

Manufacturers are managing increased demand from their customers and the pressure of keeping ahead of an ever-growing number of competitors while working to mitigate supply chain issues.

Distributors are competing for reduced cargo capacity and navigating short-term disruption to customs clearance, even before the blockage of the Suez Canal in March 2021 caused further disruption to the already-stretched global supply chains. The need to ensure cargo is on ships or that it clears customs quickly, without additional charges, can put pressure on those local agents of the distributors to push the boundaries of legality.

However, developers and operators are arguably experiencing the largest set of challenges. This group must contend with the possibility of corrupt public officials attempting to extract bribes from them in exchange for granting highly prized renewables contracts and licences. If leasing land, they also have to deal with undue influence and lobbying as a result of the vast rents payable for operating farms and generating energy using that land.

It is also reported that bribery is used to ensure that lucrative fossil fuel contracts are renewed, despite the obvious benefits to the climate of renewable energy alternatives.9 In addition, operators and developers risk being the victim of tender- and bid-rigging, with competitors colluding to keep prices high or government corruption driving out certain bids in favor of the pre-preferred provider, sometimes with attractive personal incentives secretly baked into a submission.

All should be aware that research into failed renewables projects, such as a 2017 study in sub-Saharan Africa,10 has shown that corruption present at the award process was frequently decisive in a project’s ultimate failure. This would seem counterintuitive—if corruption is present, then logic suggests these projects are approved and “protected.” Yet, this is not the case—if corruption starts early and is allowed to continue, it is incredibly hard to curb later on.

How to Address These Risks

What Can Be Done to Minimize the Risks of Corruption?

More experienced industry developers and investors have learned to make it their business to conduct a more thorough review of prospective business partners or acquisition targets and to consider an investor’s source of funds before putting pen to paper. They aim to understand the background and reputation of the counterparty and its management to ensure there is no history of bribery or corruption, an opaque ownership structure or sanctions exposure. They implement processes to verify the company’s tangible assets, such as land ownership, and review the license award process to check for concerns or untoward links between the company and public officials. Investors are also looking to understand if there are sustainability, human rights or ethical risks related to a project.

Case Study

Kroll’s client was exploring the opportunity to acquire a solar power company with operations in various continents. As part of the acquisition, Kroll was asked to conduct reputational due diligence to help the client identify the various risk points involved in this type of acquisition, such as bribery and corruption, political exposure and any state involvement in the various projects. The client heard rumors of possible inappropriate connections between the local government and one of the company’s subsidiaries in Argentina.

During Kroll’s initial research, questions were raised in the public domain about who the true beneficial owners of the Argentinian subsidiary were. It was alleged that individuals were acting as a front for a former government official. It was not possible to verify these claims through the public domain; therefore, Kroll engaged local sources on the ground to conduct additional human source work. It was identified that the former government official was the ultimate owner of the company. Furthermore, he was using his influence and connections to create shell companies to bid for renewable energy projects, including the project Kroll’s client was going to acquire. This information allowed the client to exclude the Argentinian subsidiary from the sale and avoid the corruption and undue influencing risk associated with the entity.

As discussed above, operators and developers need to be aware of the potential for corrupt public officials and rigged or pre-agreed award processes for contracts. They should consider and benchmark local partners and assess the jurisdictional risks present. Some risks can be specific to the country or region of the proposed site, such as the forced sale of land or activist protests, representing a threat of business interruption. Ultimately, the chances of a successful project are increased by fully understanding the environment in which a company is operating and using this knowledge to avoid inadvertently working on a project in which corruption is inherent.

Case Study

Kroll’s client was evaluating whether to enter into a joint venture with an Indian solar farm operator to co-manage various solar projects. The client had received details of the entity’s shareholding structure and had asked Kroll to verify it and conduct reputational due diligence on the entity and the key principals associated with the operations.

Kroll utilized in-country sources to conduct discreet inquiries in India, speaking to well-placed individuals such as experienced members of the solar power industry, former employees and bankers who could comment on the company and management team’s reputation. Kroll established that the company was in financial difficulty, contrary to what the client had been told, and was cutting costs, requesting extensions on loans and was also in the process of selling some assets. Furthermore, Kroll’s research identified a number of historic and ongoing litigation cases, posing further financial risks to the ongoing viability of the business. Kroll’s inquiries helped this client determine that the risk presented was too high and helped it avoid entering into an inappropriate agreement with the operator.

Conclusion

As the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) approaches in November 2021, governments around the world are experiencing pressure to meet the goals of the 2015 Paris climate agreement. Indeed, U.S. President Biden has already upped the stakes in the political bidding war to be the toughest on climate change, with a commitment to a 50%-52% reduction in U.S. 2005 carbon emissions levels by 2030. Other countries such as Japan and the UK have also set challenging targets, with renewable energy the common defining strategic pillar for any chance of achieving these governments’ commitments. Such massive impetus for further investment and expansion of the sector will likely lead to even greater incentives for corrupt individuals to take advantage of the ongoing green rush.

It is essential that companies active in the renewables industry are vigilant, ensuring that they know exactly who they are doing business with and avoiding the temptation to bend their own policies in the rush to achieve a perceived commercial advantage. Appropriate due diligence should be another data point to leverage during deal negotiations.

Confident mutual understanding of partners’ and investors’ true experience, capabilities and backgrounds can facilitate a trusting relationship and create the solid foundations for dynamic partnerships for competitive advantage. With various levels of due diligence available in the market for different deal stages and risk thresholds in the renewables’ lifecycle, factoring in time and budget to apply these can make all the difference to successful project planning. The ability to avoid business interruption because of financial, legal, regulatory and reputational issues is just another benefit of looking carefully before leaping into the unknown.

Sources

1 https://www.undp.org/publications/peoples-climate-vote

2 https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/energy-outlook/energy-outlook-downloads.html

3 Ibid

4 https://irena.org/publications/2021/March/Renewable-Capacity-Statistics-2021

5 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-10/the-490-billion-boom-in-esg-shows-no-signs-of-slowing-green-insight

6 Ibid

7 https://www.morganstanley.com/press-releases/morgan-stanley-survey-finds-investor-enthusiasm-for-sustainable-

8 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-04/jpmorgan-s-esg-debt-head-expects-sustainability-linked-bond-boom

9 https://www.u4.no/publications/anti-corruption-in-the-renewable-energy-sector

10 https://www.u4.no/publications/anti-corruption-in-the-renewable-energy-sector

Compliance Risk and Diligence

Complying with anti-money laundering and anti-bribery and corruption regulations.

Background Screening and Due Diligence

Comprehensive spectrum of background checks, screening and due diligence services.

Third Party and Vendor Screening

Supporting corporate third-party management programs to drive risk-based due diligence decisions.

Supply Chain Vendor Screening and Due Diligence Services

Identifying, assessing, mitigating and monitoring third-party risk in modern supply chains